#79 ON THE TOP 100 LIST

The 100-degree days started in early May 2011. They stretched on and on until 100 days over 100 degrees had been recorded. Many all-time heat records were set. Like 56 consecutive days above 100. From Aug. 16 through Aug. 31, every day was higher than 105 degrees.

Even worse for the garden centers and homeowners were the nighttime temperatures.

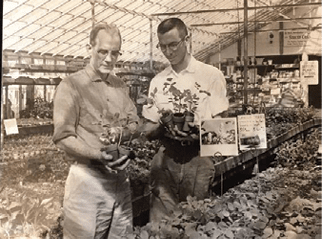

Steve Smith, my brother and co-owner of Smith’s Gardentown in Wichita Falls, Texas, remembers that we went for weeks where the night temperatures never fell below 90 degrees. “Because there were never any cooler temperatures, the heat stress on plants was tremendous,” he says. “Even watering three times a day, we could not maintain trees and shrubs in containers.”

From my desk, I could watch every day as our staff filled pallets with dead shrubs and used the forklift to carry them to the dumpsters. By the time we had logged $100,000 in dead plants, we quit counting.

To add to the distress in the family, my father, Curtis W. Smith, who had helped found the business in 1949 and managed it for more than 60 years, passed away in June. My siblings, Steve and Doug and I inherited the garden center.

Little did the people of Wichita Falls realize that the summer of 2011 was only the beginning. That same year, the reservoirs that supply drinking water to the city and the surrounding areas were at 60% capacity — probably enough to last for a while, everyone thought.

The area receives an average of 25 inches of rain per year, making it semi-arid in the best of times. Imagine the impact of a 22-inch rainfall deficit in 2012-2013. And as homeowners began to heavily water their landscapes to combat the extreme heat, the lake levels dropped.

By 2012, city leaders became concerned enough about the reservoir levels that they instituted rationing that became progressively more severe. A stiff increase in the cost of water was also designed to curb use.

“When they began talking about outlawing any outdoor watering, our plant sales basically stopped,” Steve says.

That shoe dropped in late 2012. No outdoor watering was allowed except for hand watering of containers. Homeowners began to place water buckets in their showers to catch what water they could to try to save some of their plants. Many invested in rain barrels. Most just had to watch their landscape plants suffer and die.

Signs urging citizens to “Pray for Rain” sprang up all over town.

For the spring of 2013, we greatly reduced the number of bedding plants we grew. By May, after a dismal spring, we decided to close up shop until the rains returned.

We held a closing sale at the end of May, not knowing if we would reopen. Our loyal customers wanted to help us out, and we sold all the merchandise in the store — plants, chemicals, hard goods. Then we laid off most of our employees and closed the doors for the summer.

By fall, still hopeful rain would come, we reopened the store with several truckloads of pumpkins and a small number of mums. Instead of 30 greenhouses, the company had one-third of one greenhouse full of plants. Our family stopped drawing their normal salaries, living on savings and credit cards, while selling off any equipment or other assets we could spare. Soon, my brother Doug left the business to open a landscape operation in the Texas Hill Country, where the drought was not as severe.

An SBA disaster loan helped keep the doors open but could not begin to make up for the losses.

The rains held off and the reservoirs continued to drop. Wichita Falls became known as the city drinking “potty water” because the city instituted its Direct Reuse project. Water coming from the sewer system was diverted to the water treatment plant to be treated and immediately returned to the drinking water system. There were grumbles at first, but soon citizens were thankful that the system bought them a little more time.

“By the spring of 2015, we knew we could not hold on any longer. If we did not have a good spring season, we had decided to close down for good at the end of May,” Steve says.

March, April and most of May passed with sales 75% lower than a normal year. Then, in mid-May, it rained. And rained. And rained. Within two weeks, runoff water filled reservoirs to capacity. Crowds flocked to the dams to watch blessed water pouring over the spillways.

The watering restrictions were lifted, and our customers immediately began flocking back to the nursery as we scrambled to find plants to satisfy the pent-up demand. In June, we held a Thanksgiving party on our grounds with bands, food and prayers.

As things returned to normal, Smith’s Gardentown marked record sales in 2016 and every year since. And for four years, local reservoirs have stayed about 90% capacity. Still, residents are all about water conservation.

“Folks who lived through the Great Depression changed the way they thought about money. Anyone who lived through the Great Drought here will never take water for granted,” Steve says.

And I’m trying to find out if any other business has ever taken out (and repaid) three SBA disaster loans for three different types of disasters.

Explore the December 2019 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Garden Center

- GS1 US Celebrates 50-Year Barcode 'Scanniversary' and Heralds Next-Generation Barcode to Support Modern Commerce

- Weekend Reading 7/26/24

- Retail Revival: Making gardening contagious

- ‘Part of our story’

- Registration now open for Garden Center Fertile Ground Webinar Series

- Dramm introduces new hose, sprinkler attachments for home gardeners, nurseries

- Meet the 15 Retailers' Choice Awards winners from Cultivate'24

- 2024 Top 100 Independent Garden Centers List